Full disclosure: I come to this piece, if not an opera virgin, then certainly a novice to the artform (but still a seeker of Truth and Beauty.)

When I do what I usually do – which is write about theatre – I like to give the impression that I’m a knowledgeable expert. I get away with this because theatre audiences are used to actors pretending to be someone they’re not, and I guess it’s not too big a jump for them to continue playing this fun game when they read my reviews.

But I won’t pretend expertise here. I’ll write as someone fortunate enough to have been shown a doorway to an exciting new world.

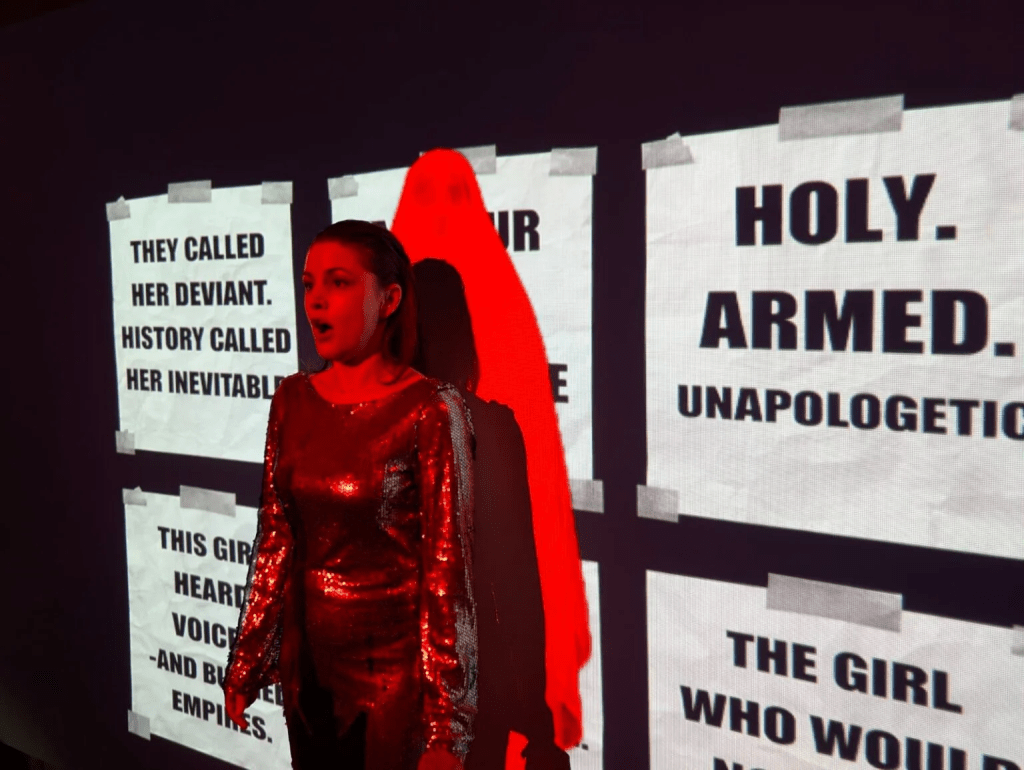

Directed by Adam Player, Possession is what I might call a pocket opera – less than an hour, and presented in a beautiful, intimate venue. It would be a marvellous introduction to the artform. (With its simple but evocative staging, it’s also a model for how opera could be enjoyed by a greater number of people than only those who can get to the Opera House and can afford those tickets!)

Mezzo soprano Ruth Strutt, accompanied by pianist Michael Curtain, presents samples from the works of Gioachino Rossini, Gaetano Donizetti and Ethel Smyth.

The Rossini is his Giovanna d’Arco, the solo cantata presenting Joan of Arc’s farewell to home before battle. It’s inspiring, it’s poignant and Strutt’s performance, in both voice and physicality, beautifully captures the character’s emotional range.

The Donizetti is his Saffo, which gives voice to the ancient Greek poet. Here Strutt has the opportunity to portray a character with even more vulnerability, and she embraces this with mesmerising passion. The Italian libretto is presented in English surtitles, as it was for the Joan piece, and it’s a wonderful chance for the creative team to use projection to establish setting and mood. Here Sappho’s lament for lost love is presented as though it were a series of text messages, and it’s a cheeky decision that underlines the universality of the experience, that Sappho’s 7th century BC concerns, via the medium of Donizetti’s 19th century opera, are still very much ours.

The Smyth pieces are her Nocturne and Possession. The latter is her work dedicated to suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst. Here surtitles are no longer necessary, and Smyth’s romantic influences are apparent. Performed with a luscious, welcoming warmth by Strutt, the melodies are rich and accessible.

Why Joan, Sappho and Smyth? These are voices of female resistance, but none has been flattened to mere slogan by the weight of opposition. Each is deeply human, acknowledging challenges while all the time reaching for joy.

Under the direction of Player, Curtain and Strutt give us a gem, a small piece that dazzles (for me, a jewel given at the threshold of a previously unexplored land, a promise of treasures, of Truth and Beauty.)

Paul Gilchrist

Possession, consisting of works by Rossini, Donizetti and Smyth,

14 – 15 Feb,

at the Substation, Qtopia, as part of Mardi Gras.

Image by Adam Player.