This is a magnificent piece of theatre.

However, I suspect the title might put off an Australian audience.

Australians like to believe we’re less literal than our American cousins. Case in point: we often joke that they don’t get irony. But, ironically, when it comes to religious language, we’re the ones reluctant to use it in any way other than literally. In many other cultures, writers comfortably evoke God without fear that it automatically commits them to the theological tenets of some religion. Religious language is employed to suggest or symbolise the grand, the awe inspiring, the universal. Sometimes, it can feel like the only discourse big enough for these things. An honorary American, Albert Einstein, was famous for using religious language in this way. His oft quoted comment, expressing his objection to quantum theory, that God does not play dice, was simply an assertion that mere chance could not be fundamental to the fabric of the universe. He was saying nothing that we unsophisticated Australians would interpret as religious.

The title of Samuel D. Hunter’s play uses religious language in a similarly evocative way. In this superbly crafted two hander, no one says a word about religion. Not a word. The two male characters discuss money, work and most of all, their children. They build an unlikely friendship. The title simply implies hope, that despite problems, things might work out OK. (I know I’m getting awfully close to spoiler territory here, but the final scene, which is a theatrical surprise and an utter delight, reminds me of the conclusion of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, only more secular. Wilder himself borrowed the idea from Dante, that towering poet who spoke of the human heart via religious language – because only it had the grandeur to do justice to his topic.)

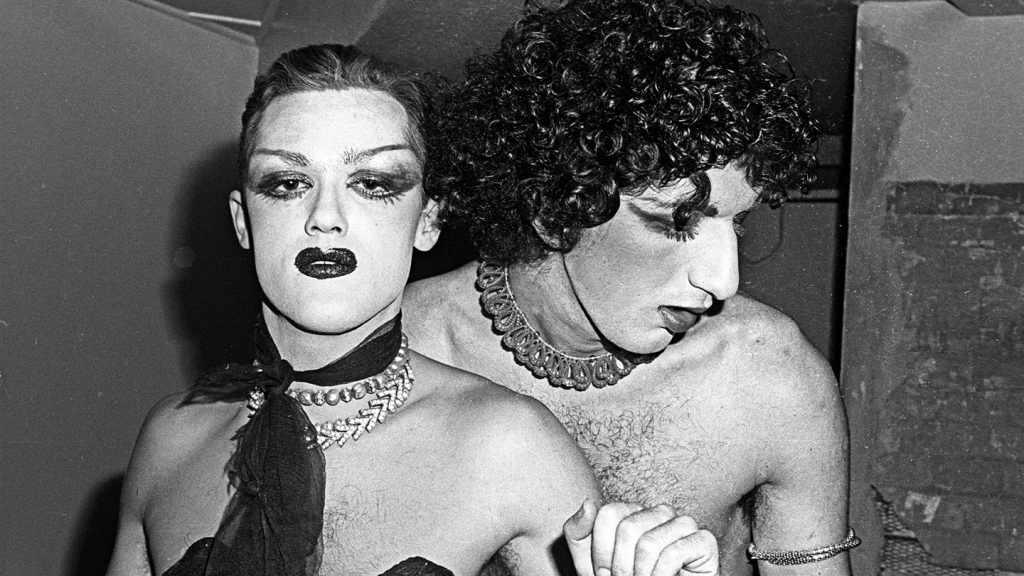

Director Craig Baldwin’s production is wisely pared back so that the focus is on the two splendid performances by Elijah Williams and Anthony Gooley.

Keith is an educated musicologist, working as a mortgage broker. As a single gay man, his dream of adoption is proving difficult, so he fosters a new born in the hope that the relationship might be allowed to become more permanent. Surviving a divorce, working class Ryan seeks a mortgage to help give his baby daughter a real home. Out of a similar sadness, the friendship between the men grows.

Williams’ Keith is brilliant: prickly, vulnerable, articulate and lightning fast. Gooley’s Ryan is marvellous: slow, awkward and inarticulate. Both characters are beautifully generous-hearted. It was pure pleasure to spend ninety minutes in their company.

A case for the existence of God? Amongst other things, it’s their friendship that suggests the possibility. (See above. God is love is not marketing hyperbole; it will reward deep reflection in a way that Coke is It cannot.)

In a play jam-packed with scorchingly truthful moments, one of my favourites is when the two men, sharing a bottle of scotch, begin to discuss the history of Western music (as you do.) Keith mentions the invention of polyphony, a term which is, of course, meaningless to Ryan. And then the penny drops: harmony! Ryan can’t believe there was a time before harmony. The symbolism is not overplayed, the scene does what drama excels at: concrete moments played so honestly they intimate something universal.

Paul Gilchrist

A Case for the Existence of God by Samuel D. Hunter

At Seymour Centre until 4 May

www.seymourcentre.com/event/a-case-for-the-existence-of-god/

Image by Phil Erbacher