Why are there so many violent children?

What do we do about them?

And how do we stop the problem arising in the first place?

Our culture assumes there must be simple answers to questions such as these. We’re certain of the destination, so there must be a path. Perhaps this attitude is a product of our hubris, or a result of the current fashion for self-righteousness. Or maybe it’s a consequence of something closer to universal, the spell of language: if you can formulate a question, then there must be an answer.

In Duncan Macmillan’s beautifully wise play there are no simple answers.

Fourteen year old Darryl is obsessed with violence. School staff member Tom doesn’t know how to help. And Rita, Darryl’s only remaining family member, desperately wants to pretend he’s just a normal teenager.

There’s a brilliant piece of dialogue between Tom and his partner, Jodi. (I’m probably paraphrasing, but this is its core)

Jodi: Who’s to blame?

Tom: No–one.

Jodi: Then what hope do we have?

Darryl also refers to this blame game.

Counter-intuitively, blame bestows hope. Blame assumes powerful dangerous forces could have been controlled, if only we’d done what was right. (As though perfection were possible in this sub-lunar world, as though we could return to Paradise after the Fall.)

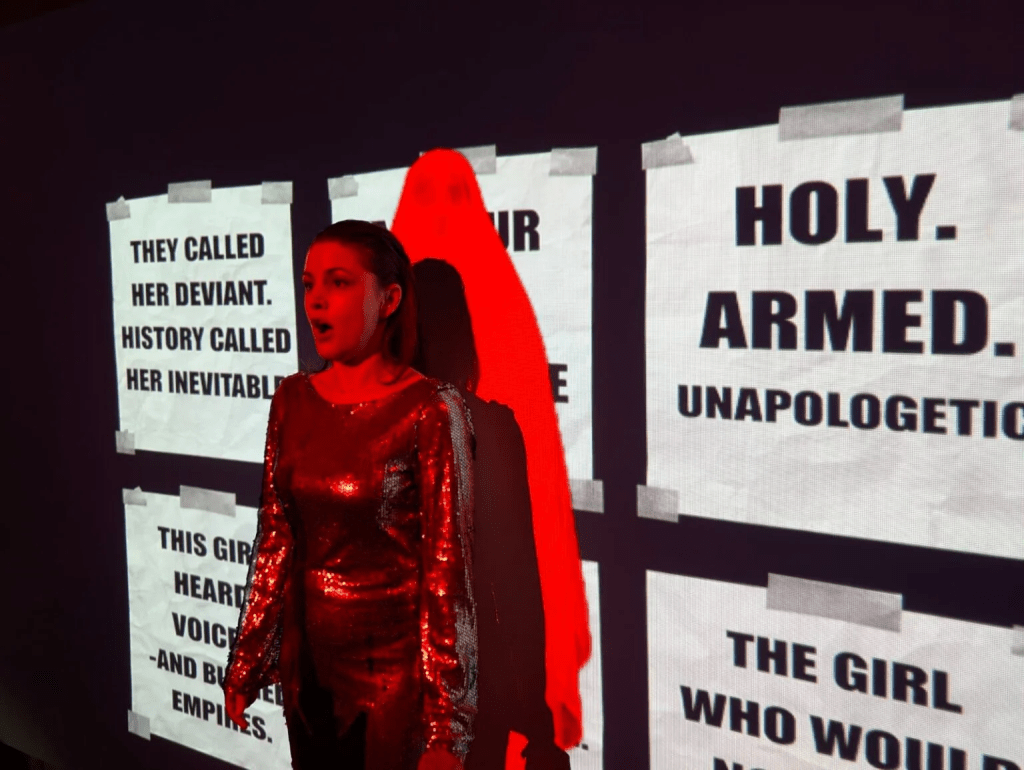

Director Kim Hardwick’s production is excellent; aided by designer Victor Kalka and a splendid cast, there’s a pared back simplicity that lays bare the complexity of the human heart. (There is one simplicity – but more on that later.)

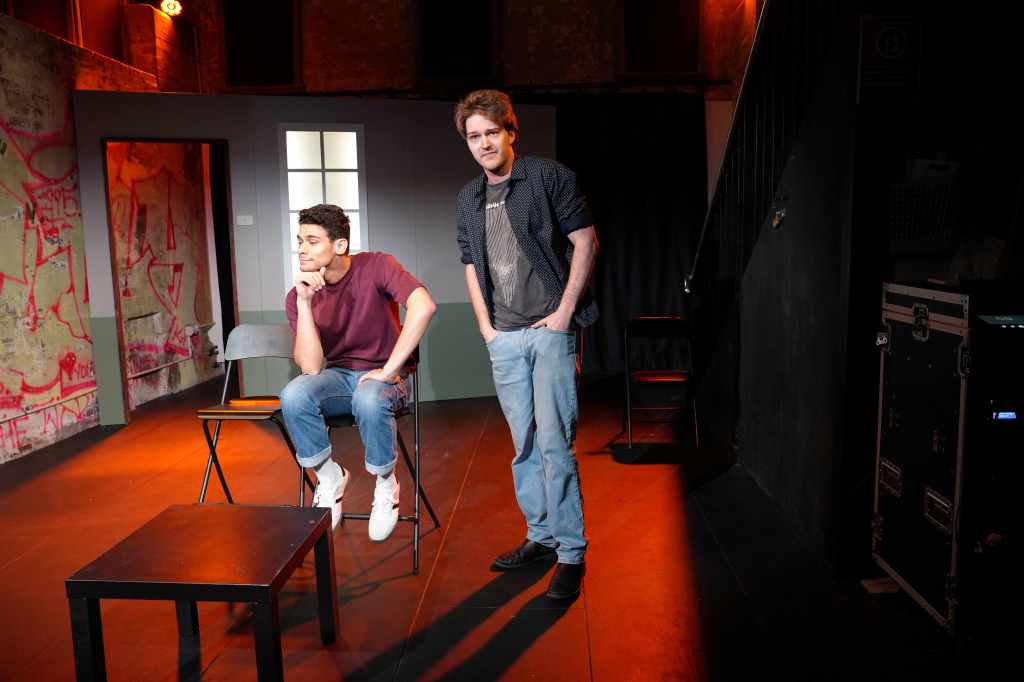

Campbell Parsons as Darryl is magnificent. Macmillan gives Darryl an incendiary idiolect – a hilarious, frightening language sourced from English working class slang and American gansta rap – and Parsons has utter command of this explosive mix. His portrayal of the troubled, piteous Darryl is an utterly fascinating and moving combination of a bouncy-youthful energy, a cynical- saddening understanding of power, and a heart-breaking innocence and self-doubt.

Having just jumped into the role a few days ago, Tony J. Black as Tom does great work, capturing the character’s struggle for patience, his bubbling frustration, and the terrifyingly all-consuming nature of the task of helping Darryl.

Romney Hamilton as Jodi gives a superb portrait of a beautifully imperfect human soul. Though creating a silly woman – one who too easily believes emotional outbursts are Truth – Hamilton still finds space to evocatively manifest the woman’s real need for companionship and security, and to express both her crushing fear and its all-too-common companion, anger.

Linda Nicholls-Gidley as Rita gives a gloriously rich performance. Confronted about Darryl, she’s defiant, even to obtusity, but also sharply loyal. And after a family loss, Rita has rediscovered her faith. It might be easy to dismiss this as mere rationalisation, and its manifestation – a fascination with angels – is cringey …. but its emphasis on Love is not. It’s the very heart of the piece. (Even Jodi, pondering the possibility that their first child might turn out another monster, asserts We will just love them more.)

So is Love the solution?

Once again, the same habit: a question expects an answer.

But, in the dark middle of the brutal wilderness that is Life, perhaps our chosen path is all the destination we can know.

Paul Gilchrist

Monster by Duncan Macmillan

presented by Tiny Dog Productions, in association with bAKEHOUSE Theatre Co,

at KXT until 21 March

Image by Abraham de Souza